Illustration of Sojourner Truth, pictured left, by Andrews University student Chloee De Leon.

The notice referred to the Dime Tabernacle, the Seventh-day Adventist congregation at denominational headquarters which was pastored by the blind Adventist minister, Wolcott Hackley Littlejohn. (3) However, the notice specified that Uriah Smith, the well-known Adventist author and editor of the Review and Herald, would officiate.

Despite this announcement, the editor of the Battle Creek Daily Journal revealed that there was some question about the arrangement of Sojourner Truth’s funeral. Also writing on the day of her death, the Journal editor affirmed that the funeral would take place on Wednesday, November 28, but stated that the “place and hour will be announced tomorrow.” The next day, Battle Creek residents learned that the location and officiant had changed; the funeral would now be in “the Congregational and Presbyterian church, Rev. Reed Stuart officiating.” (4) And that is exactly what happened. (5)

The precise details of this abrupt funeral switch are lost, but the broader picture seems clear: some of those closest to the iconic activist were carefully curating her image and legacy. Throughout her life, Truth had remained religiously independent, and it was probably supposed that a close affiliation with any specific denomination would limit her post-death influence. As a result, the Rev. Stuart, who had recently cut all denominational ties to become an independent minister, seemed a better choice for some in Battle Creek. Frances W. Titus was likely the primary controller of these revised funeral arrangements. She was a Quaker activist, Truth’s long-time friend and confidante, and manager of Truth’s correspondence and physical necessities. Titus was with Truth throughout her final illness and after her death she erected a memorial headstone for her friend in the Oak Hill Cemetery. (6)

Another actor in this drama was Giles B. Stebbins. Like Titus, Stebbins was a social reformer and Truth’s close friend. In his report of the funeral, he gave the only known contemporary answer to the funeral switch question: Sojourner Truth had requested the Rev. Stuart to conduct her funeral in his church. (7) This was probably true but does not foreclose the possibility that Truth had been gently coaxed in her feebleness to change her mind at the last minute.

Although no documentation explicitly states that Truth had originally asked Uriah Smith to conduct her funeral in the Dime Tabernacle, it is evident that she did. Two days before Truth died, the editor of the Battle Creek Moon came to visit her on her deathbed. Curiously, among other things, he wanted to know what she thought of Rev. Stuart. Barely able to talk, Truth responded, “Mr. Stuart is a wonderful man and God is working a wonderful work.” That was all Truth said, but the question was more important than the answer. It was necessary to ascertain Truth’s thoughts on Stuart because the question about her forthcoming funeral hung in the balance. The Moon editor knew this, but after conversing with Truth and Titus he left with the understanding that Uriah Smith would conduct the funeral in the Adventist Dime Tabernacle and announced that information two days later. (8)

Truth’s relationship with Adventists had grown steadily after she moved to Battle Creek in 1857. This was particularly true after 1875. Early in that year the Review and Herald publishing house offered to print a new biography of Truth and George W. Amadon, a pioneer of the Sabbath School and publishing work, worked closely with Truth and Titus to make it happen. The Adventists officially took the job on June 29 and on October 12, Amadon delivered the “proofs of the last form” for Titus to review.

But there was a problem. Although little documentation has survived, it seems that Titus wanted to cut out the pages of Truth’s “narrative” that related her Millerite-Adventist experience in the 1840s and Amadon wanted that material to remain in the new edition. So, when he delivered the final proofs to Titus on October 12, he “had some talk” with her. Apparently unsuccessful, he returned the next day “to see Mrs. Titus about [the] Second Advent anecdote.” She finally relented, and on October 14 Amadon set sixteen final pages of type for what really would be the “last form” of Truth’s new biography.

One month later, the book was published with Truth’s Millerite experience intact, but the Review and Herald received no credit for its work. Neither was Battle Creek stated as the place of publication. Boston received this honor, apparently at Titus’ request, even though neither she nor Truth lived there, and the printing had been done in Battle Creek. In fact, though the Review and Herald printed the last four editions of Truth’s biography the Adventist publishing house was not credited as the printer until the final edition appeared shortly after Truth’s death. Although Amadon and Titus had a congenial business relationship, she evidently wanted there to be some separation between Truth and Adventism. (9)

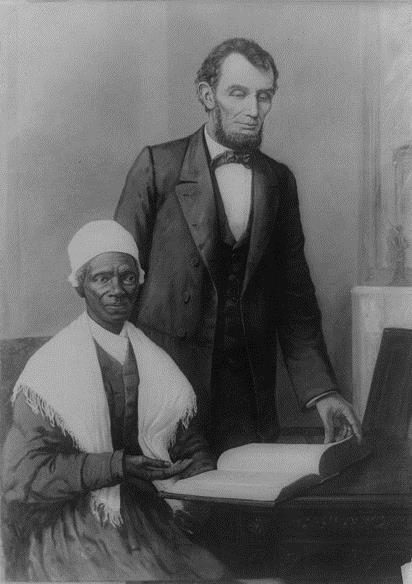

After 1875, published records from the period show that Truth occasionally lectured in the Adventist church, college and sanitarium in Battle Creek. (10) By 1882, she had grown still closer to Adventists, particularly with the doctors and nurses in the Sanitarium who regularly cared for her. Numerous Adventists visited Truth in her home throughout her years in Battle Creek and on a one occasion the sanitarium nurses gifted Truth a new dress. (11) After John Harvey Kellogg cut off some of his own skin and grafted it onto Truth’s body in a novel procedure calculated to heal her ulcerated leg, Truth gratefully remarked that the Adventists had “lengthened her days.” During her last illness, Kellogg and his medical team continued to care for Truth daily and after her death the Sanitarium proudly displayed the famous painting of Sojourner Truth with Abraham Lincoln until the sanitarium was destroyed by fire. (12)

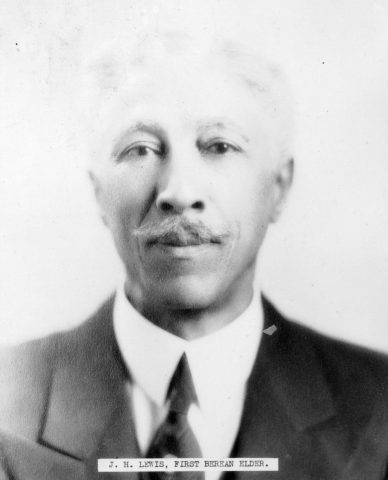

Numerous Adventist residents in Battle Creek later claimed that Truth regularly attended the Dime Tabernacle. Although it is doubtful that this happened “for more than a quarter of a century,” as one local historian claimed in the 1970s, it was probably true near the end of Truth’s life. (13) The strongest surviving evidence comes from the testimony of James Hannibal Lewis, a Black Adventist barber and resident of Battle Creek for more than sixty years. In the mid-1950s, James E. Dykes, a writer for Message magazine who spent about two years interviewing those who had known Truth, talked with Lewis. Now in his late eighties or early nineties, Lewis stated, “I recall that Sojourner Truth was baptized by Uriah Smith, in the Kalamazoo River, at the end of Cass Street.” (14) Understandably, many have doubted this account because it was published about seventy-five years after the purported incident and is not substantiated by written sources from the 1880s. (15)

Although the question cannot be definitively settled without contemporary documentation, some evidence seems to support Lewis’s claim. First, as Louis B. Reynolds noted in his earlier research, members of the Gage, Smith, Price and Paulson families confirmed Lewis’s account, asserting that Truth was a good Adventist. (16) Second, we can understand how Truth’s Adventist baptism could fit contextually, as it would explain why Uriah Smith had been originally asked to conduct the funeral in the Dime Tabernacle. Third, we can confirm that Lewis remembered the correct baptismal location. According to James White, Battle Creek Adventists typically baptized people in the Kalamazoo River and by 1878 more than one thousand Adventists had been baptized there. (17) Fourth, we can document that Lewis lived in Battle Creek during the last months of Truth’s life, which supports the common interpretation of Dykes’ interview of Lewis that his recollection was an eyewitness account. But he was neither a child nor in his early twenties as has been previously assumed. Born on January 15, 1865, Lewis was in his late teens while he lived in the South Hall boarding house and attended Battle Creek College in the early 1880s. (18) Finally, we can show that Lewis did not wait seventy-five years to reveal his knowledge of Truth’s Adventist baptism. Rather, he devoted much of his life to the preservation of Truth’s legacy and shared his memories of the Adventist Truth frequently with those who visited Battle Creek.

Lewis’ first wife died in 1926 and two years later he married Alice Beatrice Turner. (19) Alice was a civil rights activist and in the late 1920s she co-founded the Sojourner Truth Memorial Association. She served as president of this association until her untimely death in 1943 and its meetings were typically held in the Lewis home at 77 Wilkes Avenue in Battle Creek. Under her leadership, Alice actively collected written materials and living memory statements about Truth, organized programs and mass meetings devoted to promoting Truth’s legacy, attempted to place a biography of Truth in every Black school in America, and actively raised funds to erect a new monument for Truth in Battle Creek. Unfortunately, the Great Depression halted Alice’s efforts and she did not live to see her dream fulfilled. Three years after her death a marble monument—much smaller than she had envisioned—replaced the deteriorating tombstone that Titus had erected. That monument still stands today. (20)

Under Alice’s leadership, the Lewises also inaugurated the still-practiced Adventist tradition of visiting Truth’s gravesite, which lies near that of Ellen G. White and her family. Beginning in the late 1920s, the Lewises led countless visitors to the Oak Hill Cemetery and in front of Truth’s monument informed their audiences that she had been baptized into the Adventist Church and regularly attended Tabernacle services. Such visits were occasionally newsworthy, like the delegation of three hundred Adventists from the Lake Union in 1932. In covering this event, the Moon-Journal reported that Truth was an “adherent to the Adventist faith” and the Chicago Defender noted that as the Adventists placed “wreaths upon the graves of several outstanding denominational leaders, they lingered long to eulogize the memory of this great woman.” (21) Although James Lewis’s memory of Truth’s baptism was not printed until 1958, this information was widely disseminated long before that time.

James Lewis’s frequently recalled memory has credibility. Although Sojourner Truth’s faith was too eclectic to be considered exclusively Adventist despite her probable baptism, it is crucial that we uphold the Adventist Truth. Truth remains a powerful symbol of anti-racism, women’s rights, and God-ordained equity, and the Adventist Truth has rallied and strengthened many church members in the cause of social justice for almost one hundred and fifty years. Take, for example, the 1932 delegation from the Lake Union that stood before Truth’s memorial. They learned of Truth’s Adventist experience at a crucial moment—a time when Jim Crow segregation and White supremacy flourished in America and the Adventist Church. This was, in fact, the very year that the Battle Creek Seventh-day Adventist Church split along racial lines. The Lewises themselves were a part of the split, co-founding the Berean Seventh-day Adventist Church, which often met in their home or in James’ barbershop. Alice Lewis was elected the first elder of the congregation. (22)

Yet despite their frustrations, the Lewises led the Black and White delegation back to Truth with hope for Adventism and America. As White supremacy was breaking apart their own congregation, denominational leaders came to affirm the Adventist Truth before a cloud of witnesses. (23) This interracial service of reconciliation, inspired by the Adventist Truth, came at a crucial time and remains a powerful testimony against White supremacy within the Adventist Church today. If we do not intentionally and persistently fight against racism both within and outside of the Adventist Church, we will forget the Adventist Truth and fail to live it.

“Visit Grave of Sojourner Truth,” The Chicago Defender, January 30, 1932, p. 2.

Kevin Burton is director of the Center for Adventist Research and assistant professor of Church History, Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary at Andrews University.